An Unexpected Encounter

Cody shares his journey to photograph a great horned owl in the Palouse. From eager anticipation to a rare face-to-face encounter, he reflects on the patience and persistence required in wildlife photography. D

Expect nothing, feel everything — William Neill

I’m not entirely certain where my fascination with owls comes from, or when it began. Perhaps it’s to do with their use in media as wise creatures, or their elusive nature. Most of my earliest memories around them are from Harry Potter (though I have, admittedly, never seen any of the movies) and the Tootsie Pop commercials. Maybe there’s something there, but I can’t say for sure. What I do know is that I have long wanted to see one in person. Despite living aside a farm for the past decade, however, I haven’t been graced with their presence, the barn owls having not been seen in quite a while, based on what I have been told.

My desire to photograph these birds, then, became only more prominent since seeing the beautiful photographs Andrew Baruffi had managed to make while in the forests of Rochester, New York. In particular, his photograph of a small, fluffy owl—which I, unfortunately, can no longer find on his website—only exacerbated my desire to look for these creatures in my local woodland. I know the downside of expectations, how devastating they can be when you go out with a specific shot in mind and don’t find it, how easily that experience can ruin the trip. Instead, I have found it better to go out with hope, determination perhaps, but to always prioritize my enjoyment of simply being rather than basing my pleasure off any singular goal or achievement.

When I was invited out to the Palouse by John Pedersen this past June, and I noticed his photographs of owls from the area, my excitement around the possibility grew. This, if nothing else, could be my opportunity to capture a photograph of these elusive animals. Again, I needed to maintain a healthy mindset and not expect to see them, as there is no guarantee when it comes to wildlife photography. That said, throughout the first few days of the trip, I patiently awaited John’s announcement that we would be going to the barn and abandoned house where owl sightings were a possibility.

The Search

Upon pulling off to the side of the road, in front of the deteriorating barn, John told us to stay in the car and wait as he scouted the area. Guided by prior experience, he knew where the owls liked to nest and he understood how to approach them quietly enough so as to not have them disappear on us. Impatiently, I watched out the passengerside window, fingers crossed that he would see something.

When he turned back toward the car, I knew my luck had failed me: there were no owls waiting for us today.

Still, I was determined, convinced that I would photograph an owl on this trip. As I got out of the car, I chose to leave my camera behind, a tactic I often use when I’m uncertain if an area has any potential for me. This also allows me to see more freely, as I can move around more fluidly and do not feel rushed the capture a composition, if I find one.

For a few minutes, I walked around and inside the barn, noticing evidence of various birds having nested there. The walls were abstractly painted; sticks and dried grasses laid on the dirt floor; feathers stuck from the ceiling joists. Yet there were no obvious signs of an owl being there, no pellets on the ground, no dead mice left unfinished. Despite this, there was at least one other spot in the area that I could check, where I could get lucky.

Across the street sat a delapidated, two-story farmhouse, it’s once pristine white siding now mostly shades of gray. A fine subject in and of itself, though perhaps better if dark stormclouds rolled in and provided something other than the mid-day light. Either way, the house wasn’t what I was interested in. Not directly, at least. Thinking of places where an owl may make a home, I figured the house may be nice for them, filled with fieldmice and plenty of places to rest, away from people and other loud creatures. Validating this thinking, John mentioned that he had previously seen owls roosting in one of the trees to the side of the building, though he didn’t notice the usual signs of them being there.

As I walked through the tall grass, I looked toward the trees and old farm equipment, curious to see what I could see. If not an owl, perhaps I would stumble across a set of bones, a leftover meal from a coyote or vulture, always a fine photographic subject. I stopped to look at what another photographer was aiming their lens upon before turning back toward the house, trudging toward it, hopeful a snake wasn’t slithering by. There was no way I would enter the house, not trusting the structural integrity and uncertain of what was living inside, I headed toward the tree furthest back, where the owls were known to congregate at times. Even though there were no signs of their presence, I couldn’t find any other worthwhile subjectmatter, and I was determined.

The Stare

Allow me to say I have only been face-to-face with a predatory animal once in my lifetime. Even so, that was from a suitable—though not entirely comfortable—distance, and the momma black bear and her cubs were more interested in my hiking bag against the fence, and the treats within, than they were interested in me. Though that was an adrenaline-inducing incident, there was little in the way of fear involved. So, when I turned the corner of the house and felt eyes pierce through to my core, I was immediately on-edge. At the same time, I knew I had just stumbled across what I was hoping for.

Slowly turning my head, I searched for those eyes, uncertain from where they came. Of course, the unique yellow didn’t take long for me to pick out from the rest of the rather drab environment. Sitting beneath the half-fallen porch, tucked a few feet into the darkness, was a great horned owl, staring at me, wondering what, and perhaps who, I was and why I was there, disturbing its peace. For what felt like an hour, but was truly only a few moments, we studied one another, neither of us moving, our breathing steady. I absorbed that moment with the creature, encapsulated it better than any photographic device ever could. I burned it into my memory, if only because my camera was sat in the back of the truck and there was a chance this beautiful bird wouldn’t be there when I returned.

I moved quietly but quickly, my entire body vibrating with excitement. As I crossed the road, I stopped one of the other workshop participants; I asked him what lens he had on his camera and told him to wait a moment, then follow me. Together, we walked back to the owl and I shared with him the experience of seeing it, still sitting there, still wondering what was going on.

For some reason, I had decided to grab my go-to lens—the Pentax 645 120mm macro—instead of either of the long telephotos I had with me on this trip. Perhaps I thought it would be sufficient, though I quickly found it wasn’t and returned to the truck, swapping for the Pentax 645 400mm this time, as well as grabbing another participant along the way. Though I desperately wanted my photograph of the owl to be unique, I am not so selfish an individual as to not share this find with others. After a few exposures with the 400mm, I went back to the truck one last time, following the same routine as before, swapping for the Fuji GF500mm, a surprise loan from the company.

While we photographed, now a group of four, I ensured we kept our distance from the owl. Close enough to get the photographs we wanted, but not so close as to make the creature any more uncomfortable than I am sure it already was. The last thing I wanted was for it to freak out and hurt itself, let alone one of us.

This did make it difficult for me to achieve the general framing I was after, however. On the GFX50s body, the GF500mm lens is roughly equivalent to 397mm, which I thought was suitable given our proximity to the porch and owl. Whether my inability was due to an unfit desire for something unique, that was unachievable, or whether it was due to the angle at which the owl sat, slightly below and tucked away, I am uncertain. What I do know is that I had recently seen wildlife photographs where the animal is partially obscured by flora in the environment. Coincidentally, a rather large bush sat at the perfect angle for me to experiment with such a composition.

Having already captured a decent head-on photograph of the owl, I angled myself in such a way to compose what is easily my favorite photograph from the entire trip to the Palouse.

Featured Photographers

When I mentioned having seen photographs of wildlife partially obscured by flora, there are two individuals in particular I was thinking of in that moment: Murray Livingston and Geoffrey Giebelhaus (aka Dyptre Photography). Specifically, I was thinking of a trip they had taken to Kruger National Park in South Africa. I can’t recall whose photographs I had seen first, or which I was thinking of while photographing the great horned owl, but their photographs were in my mind as I tried to figure out that composition. So, I thank them both for their assistance from afar, especially as wildlife photography isn’t my usual forté.

Since this is the first time I’m featuring two photographers at once, I feel it is most appropriate to focus on the work they created while in Kruger this year, using that trip as a connecting point.

If I’m not mistaken, I came across Geoffrey’s photographs after he shared them on the LPW Discord a while back. It didn’t take long, then, for me to find Murray’s work from the trip. What I love about both these photographers is just how differently they had seen some of the same subjects, likely right alongside one another, as well as the differences in their processing choices.

A great example of this is their photographs of the Little Bee-Eater, a small and brightly colored bird which, unsurprisingly, eats a diet of bees, wasps, and hornets.

Side by side, there is little in the way of comparison, past the obvious of the bird and twig being the same. While Murray’s processing is light, almost airy, Geoffrey’s feels more natural, the colors and overall tone of the image muted.

Photographs by Murray Livingston (left) and Geoffrey Giebelhaus (right)

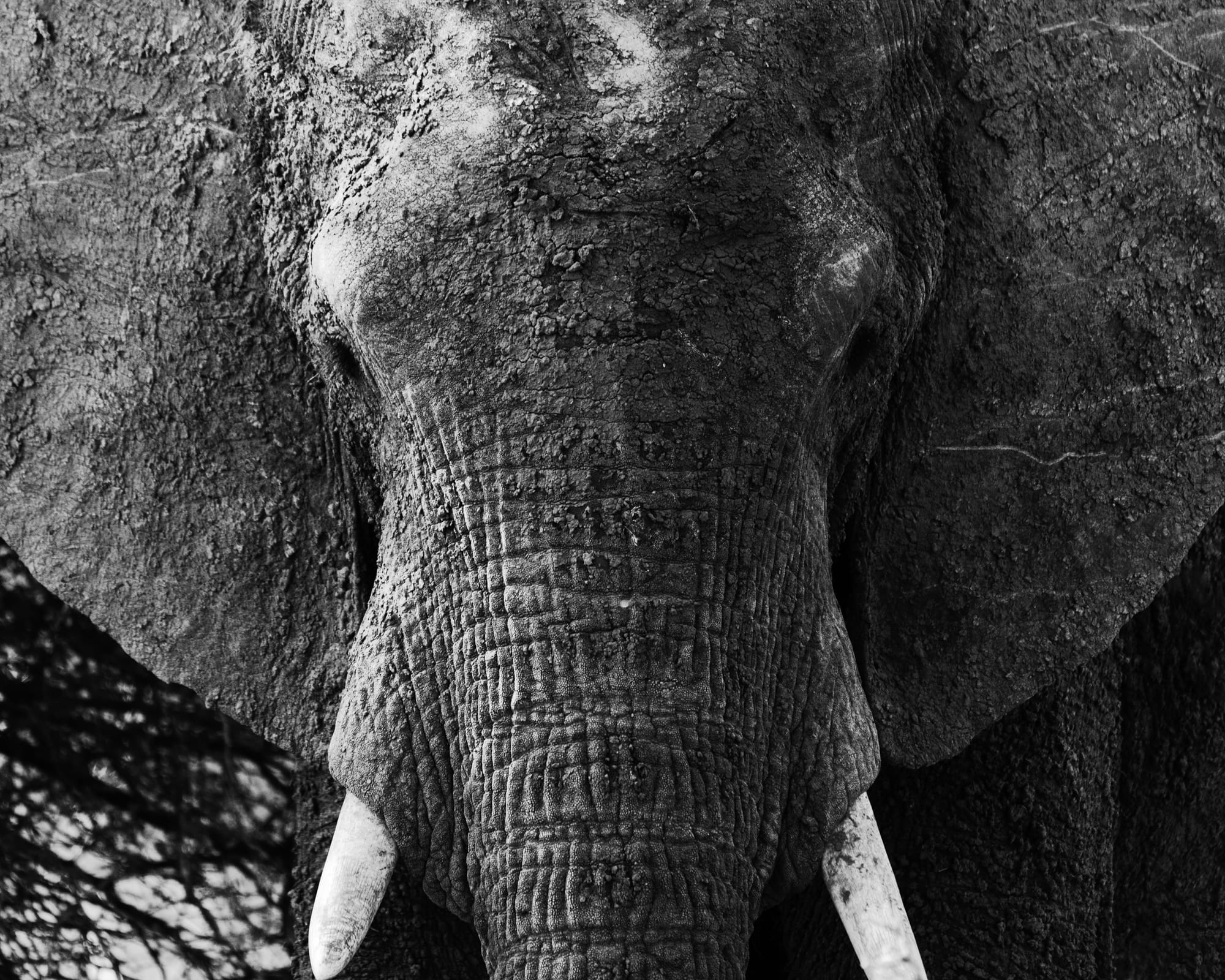

Another example, though of different subjects this time, is how they approached their black and white processing. Simply take a look at the following two images, with Murray’s on the left and Geoffrey’s on the right, and you will immediately notice how the former utilizes deeper contrast to elicit emotion from his images, while the latter has chosen to, again, keep his values more in the midtones. This time, it is Geoffrey’s image which conveys an airy feel to it, a quality which he has brought to many of his black and white photographs, both in this collection and his others.

Photographs by Murray Livingston (left) and Geoffrey Giebelhaus (right)

You can expect to find an article about Murray’s experience in Kruger National Park in the upcoming Winter 2024 issue of Nature Vision Magazine. Further, I highly recommend checking out his latest book, Machair, which chronicles his time spent photographing the dunes and beaches of the Isle of Harris, Scotland.

As for Geoffrey, you can read about his experience in Kruger via the dedicated blog post on his website. While there, I recommend you take a look at the rest of his photography; I’m particularly fond of the mushroom photographs he has made throughout the Fraser Valley.

Photographs by Murray Livingston

Photographs by Geoffrey Giebelhaus