Let It Grow On You

Explore the transformative power of printing your photographs. From boosting artistic confidence to gaining fresh perspectives, tangible prints can revolutionize your photography. Learn how living with your art deepens appreciation for your vision and helps you grow as a photographer.

The Power of Time and The Photographic Print

A photograph doesn’t feel real until it is a tangible physical object I can hold in my hand. – Stephen Johnson

I purchased my first photographic printer, a Canon Pro-100, in 2017, around the same time as my family took an inaugural trip to Wyoming and Montana. Canon was providing steep rebates on the model, which meant I could get the printer, a full set of inks, and a pack of 13x19” paper for roughly the cost of the ink set. Not a bad deal, especially for something I wasn’t certain I would enjoy using, let alone get much use out of. At the time, and even now, I don’t rely on print sales or even push the topic, so I knew this would be an expensive hobby purchase. Something to mess around with and see where it takes me.

After a few weeks of testing various papers, getting acquainted with ICC profiles and the basic workings of the machine, I printed a few of my favorite photographs from my family’s trip. I bought cheap yet usable frames from a local craft store and gifted my grandparents a set of three framed prints as a thank-you for funding the adventure. The fact that these prints, as well as the three my parents requested, still hang on their walls is a testament to the joy felt by all parties upon giving, and receiving, the gift.[1]

Since then, I have continued printing my photographs with increased frequency, amassing a sizable collection of test prints from time to time.[2] While there is still much to learn about the process and how to better improve my results, I cannot help feeling as if printing at home is seen as a waste of time and money, as not being nearly as beneficial as it has been for me. Before we get into those benefits, however, I want to discuss self-confidence for a moment, as this is a major issue many of us face as we progress as artists.

Self-Confidence as an Artist

Far too often, I hear other photographers lamenting on how they would never hang their own photographs in their homes. Some see the act as being too egotistical, as if they are inflating their self-worth by displaying their art in such a way. Others seem to self-deprecate, believing their work doesn’t belong on their walls, for it isn’t good enough. Regardless the reasoning, I always find it a bit odd when these same individuals are attempting to sell prints of their work to others. On one side of the spectrum, I question why someone worried about the inflation of their ego would want others to buy their work, thereby potentially furthering the inflation; on the other side, I wonder why someone who doesn’t believe in the value of their work would try to sell it for any amount of money at all.

While I can’t speak on the egotistical side of the argument, I can at least shed light on the detrimental effects of self-deprecation, based on personal experience.

For the longest time, I have felt as if my art means little, both to myself and others, particularly from a technical standing. Although I would be pleased with the moment I captured, often liking the composition or the tonality, it wouldn’t take long for me to stop feeling pleasure toward the photograph and begin picking it apart. Sometimes this would happen while editing; other times, it wouldn’t be until after I posted to social media. That latter aspect alone is, I believe, what has led to a lot more deprecation in the art world than is necessary, let alone healthy.

Let me preface this by saying a lot of good has come from social media since its birth. Artists such as Ben Horne, Simon Baxter, and Thomas Heaton have managed careers out of their YouTube videos alone; many others have built entire empires from sharing their work online, building a following, and benefitting from print, workshop, and tutorial sales. This doesn’t even begin to cover the opportunities for connection that such sites have provided, with people from all over the world having the chance to speak with one another, share their work and ideas, and form meaningful friendships that last a lifetime.

The downsides, however, often outweigh the good, especially as algorithms constantly change and social media platforms become less about social and more about media. In other words, when the platform prioritizes the spread of the most popular content, pushing advertisements into the faces of an unsuspecting audience, all in the name of monetary gain, you end up with an addicted user base, many of which already deal with more stress, anxiety, and mental ailments than can be thought of as healthy.

So, when a photographer of any level shares their work online, only to see a lack of engagement from their audience, it’s difficult not to blame the shared art, rather than the platform itself. This is where we begin to see a high degree of self-deprecation, not because there is truth behind the thoughts but, rather, because these thoughts act as a coping mechanism for what cannot be otherwise understood.[3] What makes these actions all the worse is that they are easy to relate to, which helps drive up engagement and feeds the system. There is a degree of humility required if you are willing to publicly bash your own artwork, if you are able to say to the masses, yeah, this photograph isn’t great, but here it is anyway. There’s something about that type of statement which makes others feel seen. And I get that, all too well.

As someone who openly struggles with anxiety and depression, and who often combats thoughts of self-deprecation about my art, I understand how much easier it is to point out the flaws of a photograph than to recognize the positives. To pick apart your compositional choices, your editing workflow, almost feels productive, in a sense. You can at least tell yourself you’re working toward being a better photographer by recognizing mistakes you made. Unfortunately, negativity is always easier than positivity; it’s why the news focuses on the bad rather than the good in the world.[4] As a species, we need to work harder to smile than to frown, but at the end of the day, you’re guaranteed to feel better for the effort.[5]

It wasn’t until earlier this year that I began to realize what this constant negative outlook on my art—and my life as a whole—was doing to my mental health. This realization happened to coincide with, but is not a direct cause of, my switching to a digital setup. There are a few factors in play here that have helped build my confidence as an artist and get me away from the constant self-deprecation I am faced with. For now, however, I wish to focus on just one of these: test prints.[6]

Test Prints as Confidence Builders

I mentioned in the beginning how I ended up with my first photographic printer and the pleasure it brought not only to me but to my grandparents, to whom I gifted prints from a very special trip. What I didn’t mention is how my perceptions of printing have grown over the years since then and how printing my photographs has helped me not only to build the craft of my art but to grow my confidence as an artist.

I don’t recall exactly where or when I first heard the idea of printing your photographs prior to sharing them with the public. Perhaps it was a YouTube video or a comment read on some online forum; regardless, I began to wonder whether there was truth in such an idea. Namely, I was curious how creating a tangible object would help you to make better art. This especially confused me, as I understood the difficulty of crafting a finely-produced print—it is one thing to send your files out to be printed by a lab, where the workers have expertise on how to help you make your work look as good as possible on the printed page, but to do everything yourself is an entirely different beast.

No matter: I would learn how to make at least passable prints of my work and test this theory for myself.

What I came to realize, quite quickly, is how much truth there is in this idea. Not only did I begin to recognize errors in my compositions and editing, I came to notice more clearly when a photograph simply doesn’t work, when it doesn’t have the same emotion or consistency I desire in my portfolio. This became even more evident as my capabilities with printing grew and my results gained consistency. By having a printed version of my photographs, I could more easily manipulate the image, turning it upside down and on its side, therefore helping me to notice major distractions and/or tonal imbalance. Further helping to notice whether the photograph works as a whole, was hanging the print on the wall—I have recently begun using print sleeves and painter’s tape instead of going through the trouble of framing and un-framing—as I could gain greater physical distance, showcasing what errors the eye may get used to (i.e., a hotspot in the frame or a lack of visual coherence between foreground and sky).

Perhaps most powerful, however, is not the immediate realizations which come when printing your work but instead, the long-term benefits.

Time as an Influence

There are at least six of my own photographs hanging on the walls of my apartment.[7] One is a 20x40” facemount acrylic from my time doing art shows; two of them are 11x14” framed paper prints; and the rest are 8x10” framed paper prints. The first is a photograph I haven’t shared in many years, since I first switched from digital to film; four of them are from various seasons of my photographic career; and two of them are from an ongoing project I have yet to share publicly. I’d like to focus on those last two, for now.

The photographs seen above are from an ongoing project revolving around Coca-Cola machines found throughout my travels. Why Coke, in particular, I’m not so sure, though perhaps I’m partial to their products. When I first began training my lens toward this subject, I had few, if any, intentions of sharing them with the masses. Instead, I felt some degree of interest in the subject and, without thinking much about it, went after it. From speaking with others, this is how a great number of photographic projects start.

As I continued with this project, off and on over the course of a few short years, I slowly began questioning my motives. Largely, this comes from what I now understand as a lack of knowledge around who I am, a question I continue to battle against. Despite knowing of at least a few other spots that may be worth visiting, I allowed the pursuit to dwindle until, eventually, I stopped it altogether. The last time I made a photograph toward this project, if memory serves me, was around two years ago.[8]

Some point shortly after making the laundromat photograph, I printed and framed it, as well as the snack version. I wanted to test whether I could live with these photographs for a while, especially as I debated selling prints and, eventually, crafting a monograph. If I couldn’t stand the pieces after a period of time, how could I rightfully expect others to hang them in their homes?[9] Initially, I expected to replace the framed prints after a few weeks, maybe a month or two. Not because I despised the images but, rather, because I would get bored with them. Instead, they continue to hang on my walls, one in the stairway and the other alongside the thermostat by my reading nook, both quite prominent places.

What I have noticed is that my appreciation of these photographs has continued to grow, not only because I have utilized test prints to ensure tonal and compositional balance, but because I have lived with them and have a deeper understanding of the project as a whole. Seeing these prints on a daily basis, I know that there is at least a possibility others would appreciate them as I have, further boosting my confidence in my vision as an artist.

And that alone is so much more important to me, so much more valuable, than any amount of technical proficiency could ever be.

An alternative perspective to this is that my family is too cheap to go out and buy décor from a craft or thrift store, so they leave the prints up so their walls aren’t bare. ↩︎

Those deemed unsuitable for potential sale are used for starting campfires. ↩︎

When I say understood, I do not mean there is a lack of awareness regarding how the social media platforms operate. These days, we are all too aware of the constantly shifting algorithms, the prioritization of advertisements and capital gain, and the fact that engagement overall is down the drain, particularly when it comes to photographs. What I mean, instead, is that we struggle to understand why things are the way that they are. We cannot fathom how we got to such a time and place, particularly when these platforms originated in such drastically different manners, when they were originally for social connection. ↩︎

https://www.livescience.com/34339-facial-muscles-frown-smile.html ↩︎

Yes, I understand how odd this may seem, but do bear with me. ↩︎

Technically, in-law suite… ↩︎

There may have been one instance more recently where I photographed a Coke machine, but I cannot recall when it was and, quite honestly, it matters little to me. The reality is that, up until the point of this writing, the project has remained dormant, with very few interactions with the subject matter, for the greater part of two years. ↩︎

This harkens back to my issue with those photographers who sell their work but refuse to hang any of it on their own walls. I can understand if you don’t have the space, but test prints don’t need to take up a lot of room, nor do they have to stick around forever. Simply living with your work for a few days can have a beneficial effect, and it proves to potential clients that you believe in your art enough to live with it, helping further boost their own confidence. ↩︎

Featured Photographer

There’s a certain joy that comes when you find a photographer who has been hiding away, slowly working on their craft in the background. Someone who doesn’t make a big deal out of what they create, who isn’t interested in making a living out of photography per se, but who continues to go out with their camera in hopes of enjoying nature and photographing the beauty they bear witness to. Dario Perizzolo is one of those individuals.

In truth, I have known Dario for a few years now, interacting with him on and off through the Landscape Photographers Worldwide Discord group. He is among the loudest of voices, in the best of ways: quick to encourage others to share their work, to help where and when he can, and to bring a teasing smile to the faces of many regular members. Yet, it wasn’t until the other week that I became more familiar with his photography. I knew that he wasn’t active on any social media platforms, but that he posted to Flickr and the group every so often, and so I saw the little he chose to share. Outside of those few posts, however, I had not realized he has his own website filled with beautiful moments of nature.

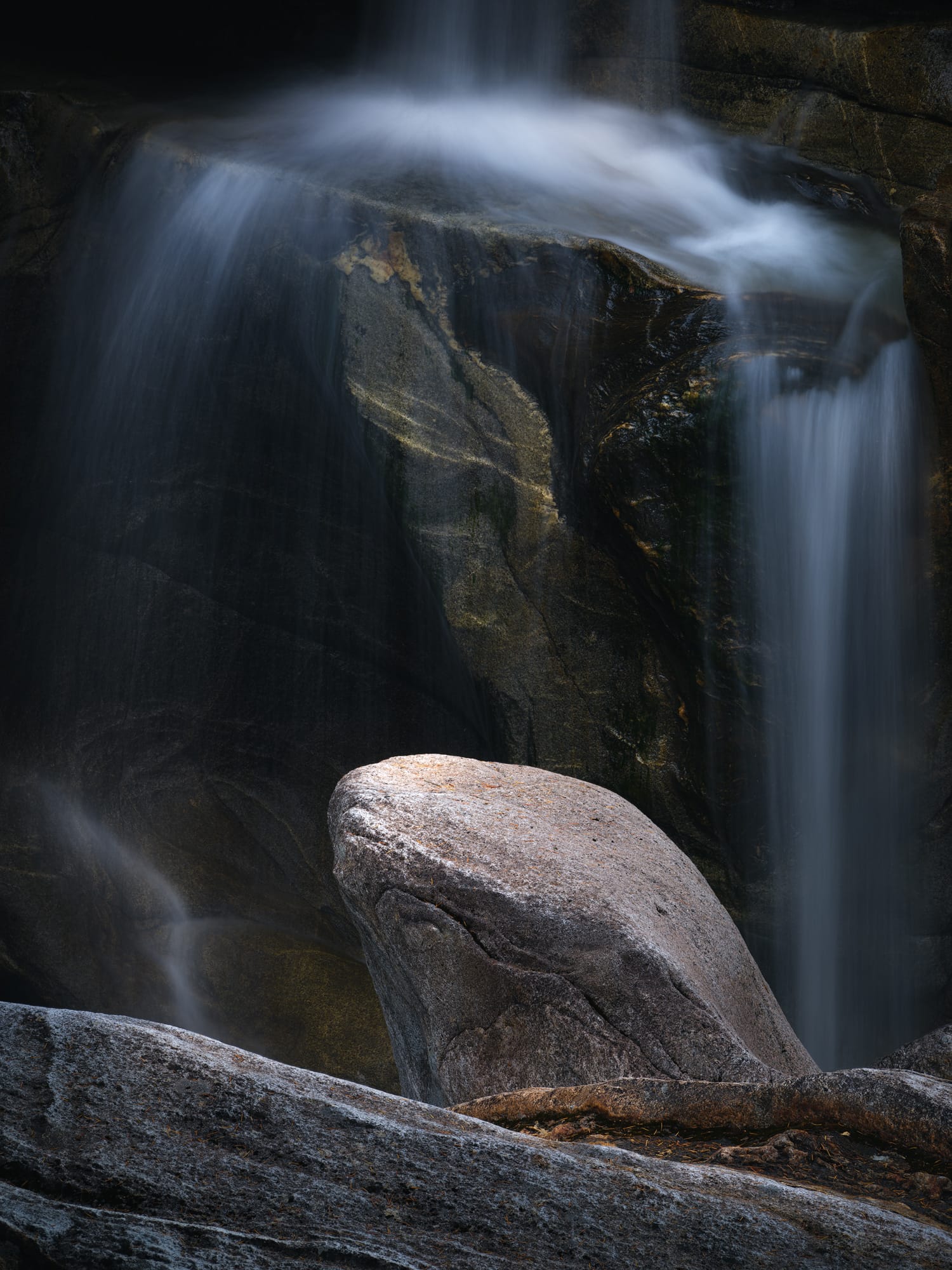

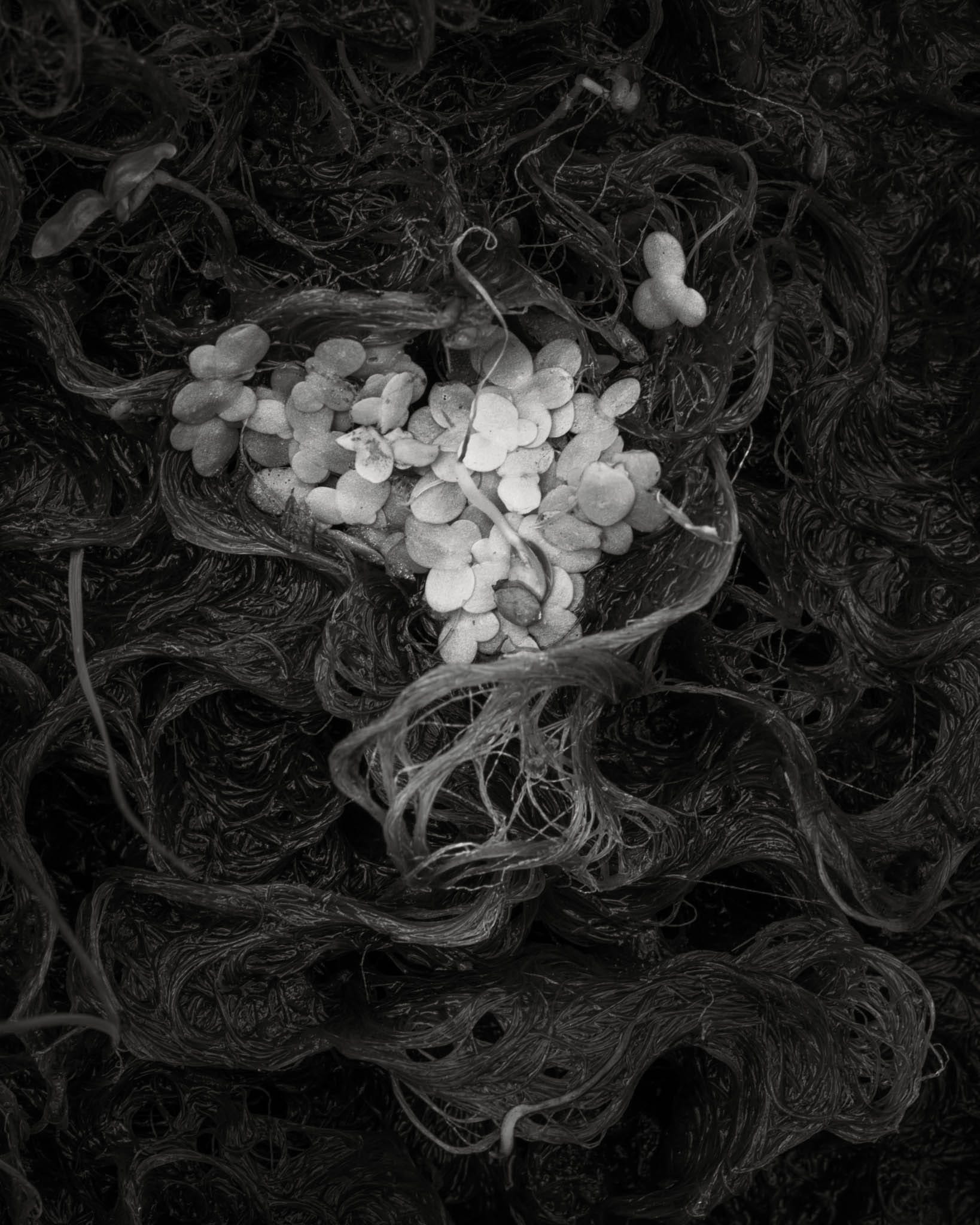

The tagline for Dario’s website is Capturing the silent power of nature—quite fitting for the intimate landscape photography he focuses on. In particular, I am quite fond of his 57KM gallery, which highlights a drive taken along a gravel logging road with a friend and the waterfalls found along the way. Despite what he says, however, only five of the fourteen photographs feature a waterfall in any prominent manner. Instead, the focus lies on the plants and rock formations, how the water provides juxtaposition to the harshness of the rock, and the last light as it highlights a moss-covered tree.

I highly recommend perusing through Dario’s website, taking the time to witness the natural world as he sees it. You won’t regret the time spent.